Irish Gifted Students: Self, Social, and Academic Explorations

Jennifer Riedl Cross, Ph.D.

Tracy L. Cross, Ph.D.

William & Mary Center for Gifted Education

Colm O’Reilly, Ph.D.

Centre for Talented Youth - Ireland

Acknowledgements

Over the past decade, many individuals were critical to the success of this project. Numerous members of the CTYI staff were invaluable for their help in gathering and entering data. Dr. Leeanne Hinch coordinated the administration of surveys and interviews in multiple studies. Rebecca McDonnell assisted in the analysis of the pandemic study. Dr. Catriona Ledwith coordinated the final edits for publication. We would also like to thank the Faculties and Senior Management in DCU for their continued support of the work of CTYI. In the US, Dr. Tom Ward provided support for the statistical analyses. Colin Vaughn, Sakhavat Mammadov, and Anyesha Mishra managed and analyzed data in multiple studies. Marialena Kostouli at the Center for Talented Youth-Greece and Dr. Paromita Roy at the Jagadis Bose National Science Center in Kolkata, India spent countless hours collecting data from students in their programs. The authors wish to thank all those who contributed their time and expertise to enhance our understanding of Irish gifted students.

Executive Summary

In 2011, Dr. Colm O’Reilly, the Director of the Irish Centre for Talented Youth (CTYI), and Dr. Tracy L. Cross, the Executive Director of the William & Mary Center for Gifted Education (CFGE) developed a partnership to conduct research with or on behalf of gifted students in Ireland. Over the next ten years, numerous studies were conducted to learn about these students and about gifted education in the country via educators’ and parents’ beliefs and experiences. Two reports have been published on the former: Gifted Education in Ireland: Educators’ Beliefs and Practices and Gifted Education in Ireland: Parents’ Beliefs and Experiences, both available from CTYI. This report describes the findings of research conducted with CTYI students for the purpose of supporting the well-being and maximization of potential among Irish gifted students. It is divided into four chapters

Chapter 1: Introduction – A description of the studies and the participating students

Chapter 6: Recommendations & Conclusions

The Studies

Ten studies were conducted with more than 2600 students attending CTYI programs, two with students in Greece and India. Nearly all participants were secondary students and 46% were female. Three studies were interviews and the remaining used questionnaires. Most students (44%) were from county Dublin, but every Irish county had some students represented. All other students scored at the 95th percentile and above.

The Psychology of Irish Gifted Students

The majority of CTYI secondary students (66%) had resilient personalities – they were sociable, agreeable, conscientious, emotionally stable, and open to new experiences. Nearly all students exhibited high levels of confidence in their academic abilities and most had confidence in all academic and social domains. About a third of students had potential risk factors indicating additional supports may be needed. These personality differences provide a framework for later analysis of students’ social and academic experiences.

The Social Experience of Irish Gifted Students

In several studies, CTYI students confirmed the findings from previous research that their exceptional abilities can lead to challenges in their relationships with others. They reported experiences of hiding their abilities and conforming to others’ behaviors to maintain positive relationships with peers. Their abilities were often visible to peers and being known as an advanced student was generally a positive experience. The frequent pressure to achieve and always be right was not as positive. Expressing one’s gifted abilities could sometimes be a costly experience and some CTYI students preferred to lie over telling the truth in situations when their abilities might be exposed. Painful peer rejection occurred for some CTYI students, but most did not consider themselves to be ostracized. They preferred to work independently and considered themselves more serious about learning than peers. Being able to help peers with their exceptional abilities was positive, but older students sometimes felt the expectation to help was burdensome. CTYI programs gave them a welcome chance to spend time with intellectual peers whose high levels of interest in learning were similar to theirs.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, online school inhibited social connections, when peers withdrew behind muted cameras and microphones and there was little opportunity to interact in classes. This atmosphere had one advantage: bullying was not possible when there was no face-to-face interaction.

Students were positive about their family relationships and most students were confident they could get support from their parents to solve social or academic problems. About a quarter of students were less confident in their parents’ support. Positive attitudes toward school were correlated with students’ positive relationships with their parents.

The Academic Experience of Irish Gifted Students

An appropriate education is important not only for students’ psychological well-being, but also for the maximization of their potential. CTYI students are capable of learning at an advanced level in some or all subjects. About half of them were confident in their abilities in all subject areas, but others had greater confidence in their abilities in either math, science, or humanities-related subject areas. In school, most CTYI students reported they rarely or never received differentiated lessons targeted at their ability level. They were often bored by lessons because they already knew the material. In interviews, students described a difficult learning environment, often focused on the needs of the typical student, who learned less rapidly and was less serious about their learning. CTYI students considered good teachers to be those with high expectations, who were enthusiastic and knowledgeable about their subjects, and had effective teaching strategies. While they may have had good teachers, they also gave many examples of times when they were not learning. Students readily shared their opinions about CTYI programs offering exciting opportunities for challenge in stimulating subjects.

Compared to in-person school, online school during the COVID-19 pandemic offered less support from teachers, was less motivating, and presented difficulties in managing their own learning. The majority of students were pleased to be back in their home school. CTYI’s online classes were perceived by students to be much more motivating and CTYI teachers were perceived to be more supportive than those in their online school.

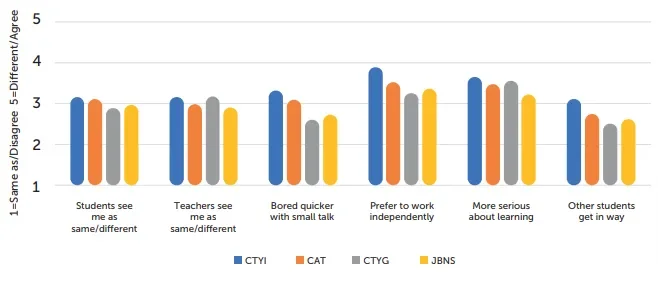

International Comparisons

Partners at the Center for Talented Youth-Greece (CTYG), at Anatolia College in Thessalonika, and the Jagadis Bose National Science Talent Search (JBNS) in Kolkata conducted studies to parallel a study with CTYI and CAT students. There were many more similarities than differences among the students in psychological comparisons. Socially, all students agreed they were more serious about learning than peers and preferred to work independently. Both CTYG and JBNS students appeared less concerned about hiding their ability from peers than CTYI or CAT students. In academic comparisons, JBNS students reported receiving more regularly differentiated assignments than the other students. While the amount of boredom differed by subject for each country, students in all programs reported being bored once a week or more often in some of their classes.

Conclusion

CTYI students represent a unique population, with social and academic experiences their peers do not share. While most CTYI students have positive, even exceptionally positive, psychological profiles, some students will require support for optimal well-being and, ultimately, achievement of their potential. Adults who work with and care for CTYI students should be aware of the social challenges presented by their abilities and the need to provide an appropriate curriculum, delivered at an appropriate pace. A talent development approach would be an inclusive, effective framework for gifted education in Ireland.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1

There has been interest in the education of exceptionally capable students for centuries. Testing has long played an important role in finding this potential, from the Imperial Examinations to identify civil servants during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE) in China (Zhang, 2017) to the IQ tests used by Lewis Terman (1925) in his study of 1000 “geniuses.”

The Centre for Talented Youth-Ireland (CTYI) continues this tradition by utilizing standardized tests to find primary and secondary students who perform at the 95th percentile and above. These students are often not well served by school systems that focus on the development of average ability students, as is generally the case across Ireland (O’Reilly, 2013). Founded in 1992 based on the model of the Center for Talented Youth at Johns Hopkins University, CTYI has grown significantly over the past 30 years. It has served thousands of highability Irish students by offering enrichment courses that expose students to topics not covered in schools, allowing in-depth exploration. A fee-based program, CTYI has expanded its offerings to low-income students through scholarships and grant-funded courses. The Centre for Academic Talent (CAT) program offers courses for students whose test scores fall between the 85th and 94th percentile, opening CTYI opportunities to an even wider swath of highly capable Irish students. The only centre for gifted education in Ireland, CTYI provides an important educational and advocacy function.

In the fall of 2010, the directors of the CTYI and the William & Mary Center for Gifted Education (CFGE) began a conversation that developed into a strong relationship between the two organizations. The mutual desire to support the needs of gifted students led to numerous collaborative research projects, publications, and presentations around the world. Previous reports have highlighted the beliefs and experiences of educators and parents (J. Cross et al., 2014, 2019). In this report, we will describe the findings of the ten studies with CTYI students and two studies with international students conducted between 2012 and 2021. Table 1.1 includes a list of the studies and Tables 1.2 and 1.3 describe participating student demographics.

Prior to 2012, very few studies had been published about Irish gifted students. In fact, only one study could be found that related to their psychology. In the mid-1990s, Mills and Parker (1998) studied students attending the new CTYI program and compared them with U.S. students participating in the Center for Talented Youth program at Johns Hopkins University. Much more is known about the psychology of gifted students in the US. Research with U.S. samples has considered their mental health (Cross & Cross, 2015; Martin et al., 2010), personality (Mammadov, 2021; Vuyk et al., 2016), self-concept (Dai & Rinn, 2008; Rinn et al., 2010), perfectionistic attitudes (Fletcher & Speirs Neumeister, 2012), achievement goal orientation (Speirs Neumeister, 2004), peer relationships (J. Cross, 2021; T. Cross & Cross, 2022), and attitudes toward their giftedness (Berlin, 2009). This research has led to a focus on the social and emotional needs of gifted students, along with recommendations for practice

One line of research began with Coleman (1985), who proposed that gifted students may encounter a stigma in society that interferes with their ability to be accepted and to develop normally. Coleman’s stigma of giftedness paradigm (SGP) has three tenets:

-

Gifted students, like all students, desire normal interactions with their classmates;

-

as others learn of their giftedness, they will be treated differently; and

-

gifted students can increase their social latitude by managing the information others have of them.

Researchers found that gifted students did, indeed, sometimes attempt to hide their abilities from peers (T. Cross et al., 1991; Swiatek, 2012). The potential of such behaviors to impact students’ psychological, social, and academic development makes this a valuable endeavor. In their influential monograph, Subotnik and colleagues (2011) stress the importance of psychosocial variables in talent development. “Psychosocial variables are determining factors in the successful development of talent” (p. 7), they claim, citing copious research as evidence.

Our primary goal in this research project has been to support the well-being and maximization of potential among Irish gifted students. By learning more about them and their experiences, we hope to provide a foundation on which to build this support in their homes and schools. The questions driving the research in this collaboration emphasized three topics in relation to Irish gifted students:

-

Their psychology, in particular, their self-beliefs.

-

Their social experience

-

Their school experience

The research has been approached through both quantitative and qualitative methodologies, allowing for a broad perspective on students’ psychology and experiences. Over the years, researchers in other talent search or gifted education programs have become interested in this project. As a result, we are able to draw comparisons with high-ability students in not only the US, but also South Korea, France, the United Kingdom, Greece, and India.

| Year | Level | No. of Participants | Method | Constructs Included |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | Primary & Secondary | 374 | Survey | Self-Concept (SDQI); Social Coping, Social Dominance Orientation |

| 2013a | Primary & Secondary | 18 | Interviews | Social Experience of Giftedness |

| 2013b | Secondary | 295 | Survey | Implicit Theory, Ostracism, Selfefficacy, Self-Concept |

| 2014 | Secondary | 163 | Survey | Self-efficacy, Ostracism, Personality |

| 2015 | Secondary | 494 | Survey | Social Cognitive Beliefs Scale, Class challenge/depth, Personality, Self-efficacy, Perfectionism, Ostracism, Implicit Theory |

| 2016 | Secondary-CAT | 351 | Survey | Social Cognitive Beliefs Scale, Class challenge/depth, Personality, Self-efficacy, Perfectionism, Ostracism, Implicit Theory |

| 2017 | International-India | 457 | Survey | Social Cognitive Beliefs Scale, Class challenge/depth, Personality, Self-efficacy, Ostracism, Implicit Theory |

| 2017 | International-Greece | 146 | Survey | Social Cognitive Beliefs Scale, Class challenge/ depth, Self-efficacy, Ostracism, Implicit Theory |

| 2018 | Secondary | 559 | Survey | Social Experience Scale, Personality |

| 2019 | Secondary | 12 | Interviews | School Experience |

| 2021a | Secondary | 326 | Survey | Pandemic Academic Experience |

| 2021b | Secondary | 16 | Interviews | Pandemic Social Experience |

Figure 1.1 - County Representation of CTYI (2015, 2021) and CAT (2016) Students

Between 2012 and 2021, the students described in Table 1.1 participated in surveys and interviews. In all survey studies, student anonymity was preserved, with no identifying information collected. Data collected via interviews preserves students’ confidentiality. Data was quite evenly distributed between males and females. To reflect changing societal recognition of gender fluidity, additional gender options were included in the surveys from 2018 on. Surveys of primary students were conducted only in 2012. The 2016 students surveyed were in the Centre for Academic Talent (CAT) program. These students scored between the 85th and 94th percentile on standardized achievement tests. All other students scored at the 95th percentile and above. In 2015, 2016, and 2021, students were asked to identify their home counties. Nearly all Irish counties, including several in Northern Ireland, were represented (see map in Figure 1.1). The majority of students were from County Dublin.

Interviews were conducted with students in 2013, 2019, and 2021. The 2013 interviews were part of a five country cross-cultural study of the social experience of gifted students (J. Cross, Vaughn et al., 2019). In each country, three male and three female students at the elementary (4th and 5th Class), middle (2nd Year), and high school (4th and 5th Year) levels were interviewed, totaling 18 students. In 2019, six male and six female secondary level students (2nd through 6th Year) were interviewed about their school experiences. The full report goes into detail with our findings, making the most of these students’ time and openness. In this brief report, we will summarize the findings of the decades-long study of students participating in CTYI programs. It is our hope that this research is of benefit to Irish gifted students and their counterparts around the world.

Chapter 2

One of the primary objectives of this research project has been to support the well-being of Irish gifted students. According to the dictionary of the American Psychological Association (APA), well-being is defined as “a state of happiness and contentment, with low levels of distress, overall good physical and mental health and outlook, or good quality of life” (APA, 2020). Well-being has rarely been studied among gifted students, but some studies have explored psychological constructs that lead to the opposite – high levels of distress – in this population (J. Cross & Cross, 2015). For example, there appears to be no difference in rates of depression among academically gifted students compared to their nongifted peers (Martin et al., 2010), although rates of depression have been found to be higher among creatively gifted individuals (Neihart & Olenchak, 2002). An analysis of four studies found levels of anxiety to be lower among gifted students than non-gifted peers (Martin et al., 2010). Studies of suicidal ideation (thinking about killing oneself) among gifted students find no difference from comparable samples in the general population (T. Cross & Cross, 2017). Depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation – these negative psychological conditions are linked in research in the general population with personality differences (Hakulinen et al., 2015; Lyon et al., 2021), self-concept (Matthews, 2014), perfectionism (Smith et al., 2016), self-efficacy (Bandura, 2001; Maddux, 1995), and even beliefs about the malleability of intelligence or personality (Schroder et al., 2015). To best support Irish gifted students’ well-being, we need to have a picture of their psychological make-up.

In the quantitative studies listed in Table 1.1, we asked students to share their beliefs about- what they are like (self-concept [2012, 2013], personality [2015, 2016]); what they can do (self-efficacy [2013, 2014, 2015, 2016]); how perfect they need to be, for themselves or others (perfectionism [2015, 2016]); whether people can change their intelligence or personality (implicit theory [2013, 2015, 2016]); and what they believe about how resources should be distributed in society (social dominance orientation [2012]). This section will describe what we learned about the CTYI students who participated in these studies. We can infer from these data what steps may be best to take to support students who may be vulnerable to negative psychological outcomes.

The most important lesson from our psychological research with CTYI students is that they are not a monolith. There is not one profile of an Irish gifted student that fits them all. This may seem obvious, but much previous research has attempted to explain the essence of a gifted student. By aggregating data, we can come up with an average profile, but such an average can be quite misleading. In his book, The End of Average, author Todd Rose (2016) described the efforts of the U.S. air force to create a cockpit that fit all pilots by using the average measurements of 4,000 pilots on 10 dimensions, such as arm and leg length, chest circumference, and so forth. After identifying the average, they discovered that not a single pilot was exactly average and fewer than 3.5% matched on just three dimensions. Keeping this lesson in mind, where possible, we have attempted to explore the data from a person-centered perspective. We first apply analyses in the aggregate, but then go deeper to examine clusters or classes of students who fit various profiles.

When we ask the question, “What is a person like?” there are many ways they can be described. We can describe their physical appearance, their abilities, their motivations, their patterns of behavior, or any number of other characteristics. Every individual is unique, but we often seek to find similarities that help us in making sense of others. Their personality, or their characteristic patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, are of particular importance to this sense-making.

In recent decades, personality research has consistently identified five dimensions: Openness to new experience, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism (OCEAN, the common mnemonic). These dimensions exist on a continuum, from open to closed to new experiences; from highly conscientious to disorganized and lacking in discipline; from outgoing (extravert) to reticent (introvert); from agreeable to disagreeable; and from emotionally stable to unstable (neurotic). Individuals will differ from others by degree on each dimension.

In personality comparisons, CTYI and CAT students from the 2015 and 2016 studies were less extraverted (outgoing) and more conscientious than the general population represented in the large international norm group. CTYI students were more introverted and less agreeable than CAT students, who tended to be more agreeable and less emotionally unstable (neurotic) than the general population. Numerous studies have found gifted students to have a stronger tendency toward introversion than the general population and this was confirmed in the CTYI and CAT samples.

Numerous studies have found three consistent profiles in personality characteristics:

-

Resilient – low in neuroticism (emotional instability), high in other traits

-

Overcontroller – high in neuroticism (emotional instability), low in extraversion (introvert)

-

Undercontroller – high in extraversion, low in agreeableness, low in conscientiousness

Resilients are flexible and adapt well to changing situations, leading them to generally be well-adjusted. Overcontrollers, who were so named because of their strong tendency to control the expression of their emotional and motivational impulses, have been found to be more likely to experience internalizing symptoms, such as depression and anxiety. Undercontrollers have the opposite tendency – they do not try to control their impulses. This personality pattern is associated with externalizing problems such as aggression, hyperactivity, and acting out.

The personality profiles among CTYI students in the 2015 study were mostly consistent with these patterns, but with important differences. Instead of having three profiles, the CTYI students had four, with not one resilient class, but two: moderate and high Resilients. Both classes of Resilients were high in the characteristics associated with positive adjustment – sociable, agreeable, conscientious, emotionally stable, and open to new experiences – but the High Resilients were very high in these characteristics. Together, the two resilient classes make up two-thirds (66.3%) of the CTYI sample. The CTYI Undercontroller class, 9.6% of the sample, was different from those identified in the literature, as well. Like those found in the general population, this group was highly extraverted, lowest of the CTYI students in agreeableness, but with a moderate level of conscientiousness, which is likely how they met the testing requirement for entry to CTYI. The majority of Overcontrollers were female (63.8%) and the majority of Moderate Resilients were male (63.5%).

CTYI students shared their beliefs about other aspects of their lives as well. The instrument used to measure students’ self-concept was the Self-Description Questionnaire I, which measured student perceptions of their Academic, Non-Academic, and General Selves. A majority of CTYI students in the 2012 study had overall high (n = 156; 44.2%) or moderately high (n = 86; 24.4%) levels of self-concept, with positive beliefs about their non-academic, academic, and general selves. Highest scores were seen among primary students and nearly all students had high reading self-concepts. Among secondary students, males had higher self-concept scores than females in most areas, with the exception of reading, parent relations, and general school.

What CTYI students will pursue as they develop will depend in part on what they believe about themselves. Self-concept is one’s perceptions of who they are, what they are interested in, and how they evaluate themselves: “Who am I?” “What do I like/dislike?” “Am I good/not good at ___?” These beliefs will likely have an impact on their academic pursuits. Another aspect of CTYI students’ psychology is their self-efficacy: their perceptions of their capability to carry out an activity (Bandura, 1986). In other words, self-efficacy is a measure of confidence in different arenas. Selfefficacy goes beyond an evaluation of one’s abilities to include their belief that they can carry out that activity, an important belief that will affect their motivation to pursue various activities. Table 2.1 presents the different areas measured by the Multidimensional Scales of Perceived Self-Efficacy scale (MSPSE; Bandura, 1989).

| Self-Efficacy Domain | Sample Item “How well can you…” |

|---|---|

| Academic Achievement | …learn algebra/reading and writing language skills? |

| Self-Regulated Learning | …plan your school work? |

| Social Self-Efficacy | …make and keep friends of the opposite sex? |

| Resisting Peer Pressure | …resist peer pressure to do things in school that can get you into trouble? |

| Enlisting Social Resources | …get teachers/another student/etc. to help you when you get stuck on schoolwork? |

| Assertive | …stand up for yourself when you feel you are being treated unfairly? |

| Meeting Other’s Expectations | …live up to what your parents/teachers/peers/yourself expect of you? |

| Enlisting Parental and Community Support | …get your parent(s)/brothers and sisters/etc. to help you with a problem? |

| Leisure-Time Skill and Extracurricular Activities | …learn sports/dance/music skills? |

Note: Response items: 1 = Not Well at All, 3= Not Too Well, 5 = Pretty Well, and 7 = Very Well

In an analysis of all the CTYI students who completed the MSPSE (N = 936), patterns of self-efficacy were identified. Nearly three quarters of CTYI students (n = 681; 72.1%; the Confident Majority and Superstars classes) were confident in all domains, with one in four being extremely confident. Highly confident in their academic and social skills, ability to be assertive and to meet others’ expectations, confidence among the Confident Majority only dipped slightly in their ability to manage their learning, garner social support when needed, and be successful in extracurricular or leisure activities. The Superstars class was confident in all these domains. The two most confident classes were made up almost exclusively of students with Resilient or High Resilient personality types, suggesting their flexibility in adapting to variable situations is associated with their confidence they will be successful in diverse activities.

One study of self-efficacy evaluated the 2015 students (N = 477) by their confidence in specific subject areas: general mathematics, algebra, biology, reading/writing, foreign language, and social studies (O’Reilly et al., 2018). While the largest subset of students had high self-efficacy in all subject areas (46% of the sample in that study), one subset (35%) had high confidence in their mathematics abilities, but low confidence in the other humanities-related subjects. CTYI students in the smallest subset (19%) lacked confidence in math, but were quite confident in science and the humanities.

Positive Perfectionism

Perfectionism, “the tendency to demand of others or of oneself an extremely high or even flawless level of performance” (APA, 2020, Perfectionism), among students with gifts and talents has been the focus of a great deal of research attention since the early 1990’s. One of the most widely accepted models of perfectionism describes three types: self-oriented (having unrealistically high expectations of themselves); socially prescribed (perceiving others have unrealistically high expectations of them); and other-oriented (having unrealistically high expectations for others). Much recent research in perfectionism has explored these three types.

Striving for perfection can be a healthy approach to demands. In fact, positive strivings have been found to correlate with adaptive outcomes, such as positive mood and emotion (affect), conscientiousness, motivation to master a task, and a sense of personal agency (an internal locus of control). In the three-dimension model of perfectionism, positive strivings may be measured by self-oriented perfectionism. Among the CTYI and CAT students from the 2015 and 2016 studies, self-oriented perfectionism was high and did not differ by program. Females in both programs, however, had higher selforiented perfectionism than males. The personality profiles differed significantly in their perfectionism scores. The High Resilients, the most adaptive and confident students, and the Overcontrollers, who tended to be less emotionally stable, had the highest selforiented perfectionism scores. These two groups had very different scores in Socially Prescribed Perfectionism, however, which is likely to result in different outcomes.

A Minority Needing Supports

The majority of CTYI students in these studies had a positive psychological profile. Two-thirds of them were confident and had desirable personality characteristics. A quarter to a third, however, may need support to bolster their self-beliefs and to flourish in their environments. Self-concept and self-efficacy develop from experiences. As a child engages with their environment, they have success or do not, they receive feedback from others: praise or criticism, encouragement or discouragement. Through these experiences, they develop beliefs about who they are and what they like and can do. Personality develops from an inborn temperament, shaped by the response of the child’s environment. A newborn with fearful tendencies may experience a caring environment in which they can thrive or a less nurturant one in which their fearfulness is exacerbated. How adults and peers respond to the developing child will affect their beliefs about themselves, and how others respond is affected by the child’s temperament.

Personality Challenges

The CTYI secondary students in the 2015 sample who were classified as Overcontrollers (24.2%) or Undercontrollers (9.6%) may experience challenges not faced by their resilient peers. Overcontrollers, a majority of whom – but not all – were female (63.8%), may be at particular risk for internalizing symptoms, such as depression and anxiety. They were highly introverted, meaning they prefer to avoid overstimulation, such as crowds and high-noise settings. Overcontrollers also tend to score high in neuroticism – they report being more likely to feeling depressed or to worry excessively. A supportive environment for Overcontrollers would recognize these differences, offering quiet spaces and activities with small groups or pairs. Professional counselors or attentive caregivers may help them reframe stressful events to reduce their anxiety.

Undercontrollers have been found to exhibit more externalizing problems, such as impulsivity, interpersonal conflict, and aggression . Their high extraversion means they would likely seek out peers to interact with, but their high disagreeableness may make it more difficult to develop friendships. These students may benefit from social skills training and positive feedback when they behave in a friendly manner. Their impulsivity can make peers uncomfortable. Teaching self-regulation directly and rewarding such behaviors may support Undercontrollers in developing friendships. Undercontrollers at CTYI were highly conscientiousness, which suggests they will have protection from some of the difficulties found among undercontrollers in the general population.

Self-Belief Challenges

Poor self-concept was found in 19.3% of CTYI students in the 2012 study, which included primary students, who tend to have positive self-concepts. Some CTYI students in the study had high self-concepts in all areas except their physical abilities. Self-concept can be boosted with affirmation, but having actual opportunities to succeed is more effective in changing self-beliefs. Challenge is important for these capable students, but succeeding at incrementally more difficult tasks at a lower level – working up to the ultimate challenge – will be better for self-concept development than repeatedly failing by attempting the ultimate challenge to start. In all cases, adults should be attending to what the child needs.

Academic self-efficacy was high among the CTYI secondary students and three of the classes with high self-efficacy included the majority of students: the Confident Majority (high self-efficacy across the board), the Confident Pushovers (high in all areas except ability to resist peer pressure), and the Superstars (very high in all areas). Three smaller classes, however, had less positive profiles. The Pushovers, the Insecure, and the Need a Boost classes made up 22.3% of the students in the 2013-2015 studies (N = 936). The Pushovers (n = 25) had relatively low scores overall, but were notably least likely to say they could resist peer pressure to engage in troubling behavior. The small group of Insecure students (n = 18) did not have concerns about peer pressure, but they had low self-efficacy in all other areas, with the exception of academics. The Need a Boost class (n = 165) lacked confidence in their learning skills, their ability to get help from others, and to do extracurriculars. In other areas, they had more confidence, but it was modest. An emphasis on how to get support from others would be beneficial to CTYI students in all three low-confidence classes: recognizing resources, learning how to ask for help when they need it, general social skills training.

Perfectionism Challenges

While self-oriented perfectionism has been found to be associated with positive outcomes, socially prescribed perfectionism has been linked to negative outcomes, including maladaptive motivational goals, negative affect, neuroticism, distress, eating disorders, and anxiety. The perception that others are expecting you to be perfect can be debilitating. Students in the Overcontroller class, who were high in positive expectations for their own perfection, were also high in their belief that others expect them to be perfect. These students, primarily female but including several males, are likely to be in need of psychological support.

Adult behavior, particularly that of parents, has been implicated in the development of perfectionistic beliefs, both positive and negative. Children may learn to strive for perfection or to be concerned about being evaluated negatively by observing the model of significant others or through being rewarded for such striving or punished for not doing so. They also learn through their own experience of striving for excellence, by thinking about what has occurred. Parents have an important role in their child’s development of these concerns. Their responsiveness to the child’s needs is critical to developing positive attitudes about their efforts to achieve. Research has supported the most positive outcomes for children raised with a balance between parents’ demandingness and responsiveness. An excess of demandingness in parenting may contribute to an unhealthy concern that others are evaluating you. Responsive parents are willing to give in to their child at times, realizing that their child needs to have confidence in their own ability to make choices and affect their own lives. Such a sense of agency will not develop if parents are constantly demanding. Table 2.2 describes the path parents set for their child through their modeling, responsiveness, and demandingness. It is important to note that all contributing factors highlighted in Table 2.2 are based on the child’s perceptions. An outsider may see a behavior as demanding or a model as positive or negative, but the child’s own perceptions of the behavior or model are what matter.

| Outcome: Positive Striving | Outcome: Negative Concerns |

|---|---|

| Parent expectations for high standards (demandingness) | Parent expectations for high standards (demandingness) |

| Parent models striving with positive attitudes toward failure / mistakes as part of learning | Parent models concerns with negative/ fearful attitudes toward failure / mistakes |

| Parent encourages high achievement via warm, positive messaging (responsiveness) | Parent demands high achievement via harsh, critical teaching (demandingness) |

| Parent is accepting of child’s efforts | Parent is rejecting of child’s efforts |

Adapted from Fletcher & Speirs Neumeister, 2017

Many people believe that human characteristics, such as intelligence and personality, are fixed within a person, but substantial evidence indicates that, while generally stable, one’s intelligence is affected by resources (e.g., exposure to books, access to technology, experience with excellent teachers, etc.) and that many aspects of one’s personality can change in response to the environment. Dweck (2006) found that students who held the belief that intelligence was fixed (e.g., “I am smart.”) were less likely to persist in the face of a difficult task, while those who believed it could be changed with opportunities for learning and practice were more likely to continue trying. She called these beliefs a growth mindset. Many schools have implemented programs to teach students about the significance of effort in achievement, attempting to overcome students’ fixed mindsets.

Among CTYI and CAT students, average scores were below 3.5, the point where beliefs would be considered “fixed”. CTYI females had more fixed beliefs than the males in both CTYI and CAT. All students had slightly stronger beliefs in the fixedness of personality. Implicit beliefs were not different among the personality classes, but both the Pushovers and Confident Pushovers had the most fixed beliefs about intelligence. Learning about how both intelligence and personality can change may help these students who claimed to be unable to resist peer pressure.

Chapter 3

The ability to have positive, lasting significant relationships is a critical human need. People of all ages are motivated by this need4 . They will avoid activities that come between them and people with whom they have (or wish to have) a connection and they will pursue activities that foster relationships.

Being excluded from peers contributes to increased aggression, anxiety, and depression. Even expecting to be rejected by peers can lead to social anxiety and withdrawal. One study found the experience of pain associated with social rejection is similar to that of physical pain. Students in the “brain” crowd of one study had an increase in internalizing distress as they transitioned from childhood to adolescence, suggesting these students faced uniquely difficult stressors.

CTYI students have intellectual abilities different from their peers, as evidenced by their exceptional scores on standardized tests. They may not have intellectual peers in the same classroom or even the same school, creating challenges to friendship formation. Studies of popularity have found that high achievers in primary grades are often popular, but in secondary classes high achievers are less likely to be considered popular. Significant research, cited in Volume 2, Chapter 3, indicates potential challenges to friendship for CTYI students. Considering the importance of friendship to thriving in school, an important component of our studies with CTYI students focused on their relationships with peers.

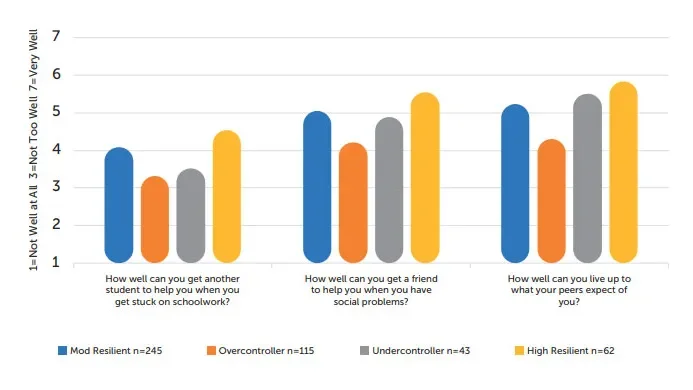

Figure 3.1- Self-Efficacy Peer Items by Personality Class (2015 CTYI Students)

Most CTYI students believed they had positive relations with peers, especially those with positive self-concepts in physical appearance and abilities. They had confidence in their ability to make friends “Pretty Well,” to stand up for themselves among peers and to resist pressure to engage in unacceptable behavior. About 20% of students did not believe they could stand up for themselves or resist peer pressure, however. On average, CTYI secondary students believed they could get help from peers to solve a social problem, but they were less confident they could get help from a peer when they were stuck on schoolwork. Students in the Overcontroller personality class were less likely than others to believe they could get help from peers on social problems and also were not confident they could live up to peers’ expectations (See Figure 3.1).

A majority of CTYI students did not consider themselves to be ostracized; they did not believe they were ignored or excluded by peers. Many of the Overcontroller students who were highly introverted, did believe they were at least sometimes ostracized by peers. Students in the low self-efficacy classes – the Pushovers, the Need a Boost, and especially the Insecure – were more likely to perceive they were excluded than their more confident CTYI peers.

In the early 1980’s, Larry Coleman and Tracy Cross spoke with hundreds of gifted students participating in the Tennessee Governor’s Schools about their social experiences. Coleman had previously proposed that giftedness is stigmatizing, and gifted students know that if others become aware of their exceptional abilities, they will be unable to have normal social interactions. From conversations with the students, Coleman and Cross (1988) learned about the conditions that led students to manage information about themselves so they could have normal social interactions and how they went about it. Gifted students might allow their abilities to be highly visible; or they would disidentify from their giftedness, behaving in ways counter to how they perceive a gifted person would, such as rebelling; or they would attempt to make themselves or their giftedness invisible. One thing that came up repeatedly in their interviews was students’ belief that they were different from peers. To further study this phenomenon, Coleman and Cross created a questionnaire that was modified for research with CTYI students. In the first part, questions asked how they believed others see them (the same as other students or different from other students) and how they considered themselves different from peers. Once again, the personality classes responded differently.

Overcontrollers and Undercontrollers were more likely to believe they were seen as different. Overcontrollers agreed most strongly that they get bored more quickly with small talk than others. Although the High Resilient students considered themselves most serious about learning, they did not believe peers get in the way of their learning. Undercontrollers, who were least agreeable, were also most likely to say other students get in the way of their learning. All CTYI students agreed that they prefer to work independently. CAT students had similar scores, except when it comes to viewing other students as getting in the way. They did not generally agree.

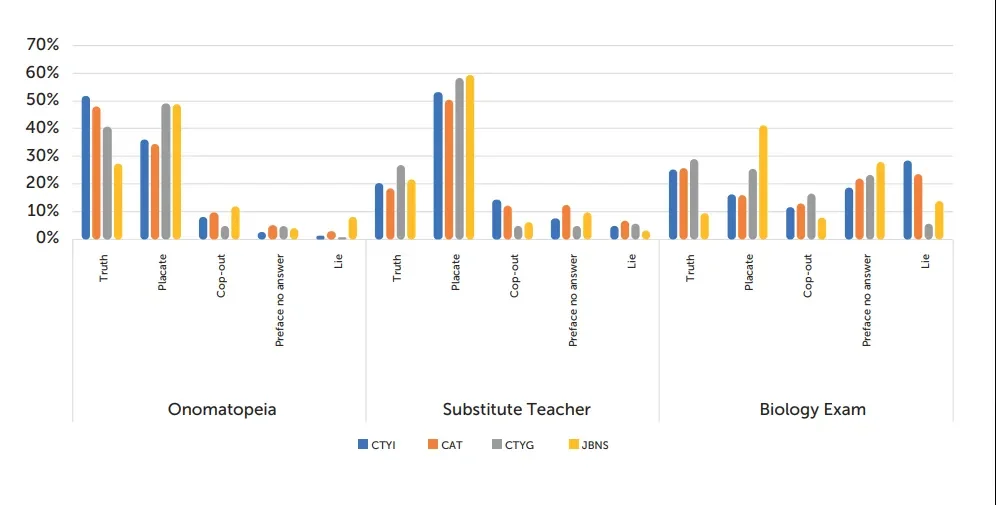

The second part of Cross and Coleman’s questionnaire was based on their findings that the conditions under which the stigma of giftedness had its effects differed. Some situations were more threatening to being “outed” as a gifted student than others. They tested this finding quantitatively with a series of scenarios, carefully crafted to elicit a response to these varying threats. The least threatening situation was to publicly show they know a discrete fact that other students did not. The scenario they created was of students complaining about not knowing the meaning of the word onomatopoeia. Asked how they would respond if they knew the meaning, students could choose options along a continuum of telling the truth to lying. The response options were developed from information given in student interviews. Students may deflect attention from their true beliefs (truth) by placating (agreeing with some aspect of the comment, before exposing true feelings), copping out (changing the subject), or covering up by using words that are related to the conversation, but do not reveal anything about the person’s self, or by giving a false response (lying). Another threatening scenario described a situation when others were not interested in learning, but the gifted student wanted to learn. For this situation, a scenario describes a substitute teacher being taunted by peers. The most threatening exposure is in the Biology Exam scenario, where others are complaining about the difficulty of a test the gifted student found easy. Cross et al. (1991) found many students responded to the Onomatopoeia scenario by saying they would tell the truth. The majority of students indicated they would placate in response to the Substitute Teacher scenario. The Biology Exam elicited the broadest range of responses, with some students comfortable telling the truth, but more being likely to cop out or even lie. Scenarios from the 2015 and 2016 surveys are below.

Scenario #1

Setting: In the cafeteria line, several people from your class are discussing the life science exam.

Taisce: Man! Wasn’t that test impossible? I must have spent 10 minutes trying to think of examples of the major biomes.

Corey: I blew the whole thing, even though I studied really hard.

Devin: I probably failed it too.

Devin says to Shannon, “I bet you breezed through it and didn’t even open the book to study.” Actually, Shannon spent several hours studying and thought it wasn’t a difficult test.

If you were Shannon, what would you be MOST inclined to say?

Please circle your choice.

| A (Preface No Answer) | B (Lie) | C (Placate) | D (Truth) | E (Cop-Out) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Tests can be hard sometimes.” | “Yeah, that exam was a pain.” | “I probably studied as hard as you did, but the test wasn’t too hard.” | “I thought it was kind of easy.” | “How long did you study?” |

Scenario #2

Setting: A group of students is discussing a class lecture as they leave the classroom.

Brady: I think it’s crazy that Mr. O’Reilly expects us to remember all of that material in Chapter 10 for the test in Literature!

Kieran: What does he think – that we have nothing better to do than memorize that stuff from the book?

Quinn: Some of those words are hard. I don’t even understand what he means by “onomatopoeia,” do you guys?

They all shake their heads, with the exception of Jamie (who has said nothing to this point). They turn to Jamie. Quinn says, “How about you, Jamie? Knowing you, you probably know it. Right?”

Jamie understands all of the terms and knows that onomatopoeia is nothing more than a word that describes a sound.

If you were Jamie, which would you be MOST inclined to say?

Please circle your choice.

| A (Truth) | B (Placate) | C (Cop-Out) | D (Preface No Answer) | E (Lie) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “It means a word that imitates a sound, like ‘crash’ or ‘bang.’” | It’s hard to remember those words, but I think it means a word that describes a sound, like ‘crash’ or ‘bang.’” | “I think you’re right, Mr. O’Reilly is expecting too much.” | “It’s not easy to remember those terms, no one can keep them straight.” | “I have no idea what those words mean, either.” |

Scenario #3

Setting: In the hallway, between classes:

Pat: Wasn’t that substitute teacher for Mrs. Flannery awful? I couldn’t figure out what she was trying to say about the Western Expansion. She really lost me.

Reagan: How about what Pete pulled on her, pretending he was sick and ready to throw up on her desk?

Aidan: She even believed it. I wish I had thought of that one! I would rather have spent the period in the clinic instead of sitting in that class. Everyone but Kelly nodded their heads in agreement.

Reagan looked at Kelly and asked, “Didn’t you think that was hysterical?” Kelly felt that the substitute had started an interesting topic, but Pete had made it impossible for her to teach. Kelly thought Pete had been unnecessarily rude.

If you were Kelly, which would you be MOST inclined to say?

Please circle your choice.

| A (Cop-Out) | B (Placate) | C (Truth) | D (Preface No Answer) | E (Lie) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “I wonder when Mrs. Flannery is coming back.” | “Some of it was funny, but Pete shouldn’t have gone that far.” | “I thought the class got out of control, Pete went too far.” | “Pete can be funny sometimes.” | “Pete was funny. The substitute was asking for it.” |

Figure 3.3 - CTYI and CAT Scenario Responses (2015 & 2016 Data; N = 852)

CTYI and CAT students responded similarly to the scenarios (see Figure 3.3). As in the 1980’s study, there were more truth-oriented responses in the Onomatopoeia scenario, more placating in the Substitute Teacher scenario, and a variety of responses in the Biology Exam scenario. Notably, 26% of the Irish students chose the “lie” option in the Biology Exam scenario, versus 12% of US students in Cross et al.’s (1991) study. The implication is that there is a high social cost to have one’s giftedness exposed to peers among CTYI and CAT students. Interestingly, the more students believed they were seen as different from peers and were less like them, the less likely they were to respond evasively to scenarios (i.e., tell the truth). This was most true in the Substitute Teacher scenario and CAT students had stronger correlations than CTYI students. As they more strongly agreed that they preferred to work independently and were more serious about learning than their peers, the more likely they were to choose more truthful options about Petey disrupting their learning. Conversely, as they preferred to work with peers or did not agree they were more serious than peers, they were more likely to hide their true feelings from peers and chose less truthful options.

To help us better understand the social experience of gifted students, the cross-cultural study of 2013 explored this topic. In the 90 interviews conducted across elementary, middle, and high school aged5 , gifted students in five countries (Ireland, United States, United Kingdom, France, and Korea), the social experiences described fell into six themes:

Positive Competition was only seen among UK and South Korean students, but the other themes described common experiences of all the students. Table 3.1 gives examples of CTYI students’ comments in each social experience theme.

-

Awareness of Others’ Expectations

-

Pressure

-

Concerned About Peers’ Feelings

-

Comfortable Among Gifted Peers

-

Confused by Response of Peers

-

Positive Competition

In the study, Irish primary school students were classified as elementary, Irish secondary school students at junior cycle as middle school and Irish secondary students at senior cycle as high school.

| Theme | Participant ID | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Awareness of Others’ Expectations | IRMM2 | Sometimes after football training my Dad would ask me a maths question and I might get it wrong because I’m tired. And he would be surprised about this and also in school my teacher would be very surprised if I get anything wrong which puts extra pressure on me and raises expectations. |

| IRMF1 | The teacher was disappointed in me which made me a bit annoyed and sad. | |

| Pressure | IRHF1 | It’s a struggle with school where girls in my class will just comment on it. If they get above me in a test, it’s a big thing for them and they really, they don’t let it go. Constantly there’s pressure there to do well just so you’re not pointed out in class for not doing well. |

| IRMF1 | That’s why I don’t think it’s good to be the best, even though I want to be, because everyone expects a lot and when you don’t reach it, people are disappointed. | |

| Concerned About Peers’ Feelings | IRMF1 | If they asked me if I found it [an exam] easy, I’d say it wasn’t that hard. I’d say I tried and I hope I do well but I wouldn’t straight out say it was so easy and I can’t believe you found it so hard because that’s just mean. Q: Why is it mean if it’s the truth? A: Even though you finding it easy made you feel good about yourself, if you put someone down for finding it hard. Finding it hard was stressful enough anyway so you’re just adding to the badness. Q: You’re worried about hurting people’s feelings? A: I think it’s because I was bullied for my intellectual abilities so I don’t want to be mean to people because of theirs. |

| Comfortable Among Gifted Peers | IRHF1 | I was really shocked. It was strange. My first class in Novel Writing we were discussing Ulysses and what was wrong with Twilight and it was crazy. Everyone had very similar interests to me and I fitted in very quickly. |

| Confused by Response of Peers | IRMM3 | Sometimes they make a bit of fun of me because I always know the answer. It’s not just me though, as they make fun of people who don’t know any answers. It doesn’t make sense really. |

| IRHF2 | I have a few friends who say that “2 weeks after DCU, you can talk about it but after that if you mention it I won’t talk to you”. I find that quite offensive because they have friends outside of school and they talk about them and I don’t give out about that because people have other friends but they don’t want to talk about CTYI because they don’t want me to and I think it’s a bit much. |

Note: Participant ID is country code (IR=Ireland), age group (E = elementary, M = middle, H = high), sex (F = Female, M = Male), and subject reference number (1–3).

The stigma of giftedness was evident in all the countries of this study. Irish students’ comments can be seen in Table 3.2. Students clearly wanted to have normal interactions, but were inhibited in some ways connected to their high abilities. CTYI students were keenly aware of their visibility as highly able and many reported being rejected by peers. Bragging, being “boasty,” was viewed quite negatively by many of the students in the study. Concern for peers’ feelings was often given as a reason for not drawing attention to one’s performance.

| Subtheme | Participant ID | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Awareness of Visibility | IRMF3 | I’m proud of being a nerd. Overall it is a positive experience |

| IRHM1 | Your reputation precedes you. When you get introduced to things and they’d say this person did X and Y and you’re seen as that rather than who you are. You don’t want that to be seen as what defines you. You want to be seen as who you are | |

| Rejection by Peers | IREF2 | My friend asks me for an answer and I tell her that I can’t tell her because it’s a test, sometimes, she like, doesn’t play with me anymore |

| IRHM3 | Sometimes if I’m trying to be friends with someone and I’m smart, they might reject me a bit. They’re more interested in being friends with someone who’s good at sports or music. | |

| Awareness of Jealousy | IREM2 | I don’t talk about it [my abilities], just like, in case there’s people who might be jealous, so I just keep it to myself. |

| IRMM3 | Some of my friends are not that happy about how well I do in tests. I wouldn’t mind, it’s mostly the ones who are smart themselves. They can get obsessed with doing better than me. | |

| Few Close Friends | IRHF1 | They just have me around for a laugh over a random fact. I don’t have any close friends I could talk to. I’m almost comedic to them. They find me a bit of a laugh. |

| IREM1 | At school, I don’t have many friends and that’s probably because of my ability. | |

| Avoid Bragging | IRHM3 | I don’t like to flaunt my results and make people feel bad. |

| IRHF3 | I think I’d feel like I was bragging because others found it difficult and I wouldn’t want them to feel bad because they clearly worked hard. |

Note: Participant ID is country code (IR=Ireland), age group (E = elementary, M = middle, H = high), sex (F = Female, M = Male), and subject reference number (1–3).

The ways in which CTYI students cope with the stigmatizing effects of giftedness were consistent with those of students in the other countries. They hid their talents, conformed to others’ behavior, helped peers when they could, and focused on themselves without regard for what others were expecting from them. Table 3.3 includes examples of CTYI students’ coping strategies.

| Theme | Participant ID | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Hiding | IRHF1 | My English teacher, because I’m good at essays, keeps pointing it out to the class and I’ve started not completing homework assignments because she always reads out mine. |

| IRMM3 | I’m trying to deflect attention away from myself. I can gauge their answer and fit mine in to what they tell me….It’s easier not to draw attention to yourself. | |

| Conformity | IREF3 | I don’t really think that I’m special and all. I just try and fit in. |

| IREM2 | Well, I…I just try and act like I’m just like everyone else. | |

| Helping | IRMM1 | I help people with stuff. They ask a lot of the time. If they’re stuck on homework they might ask me. |

| IRMF1 | They slag me but I think they appreciate that I’m smart because I can help for tests and stuff and in class I can help them as well. | |

| Self-focus | IRHF2 | I’d rather feel under pressure from myself than other people because when it’s from others, you can’t fix it. |

| IRHM2 | You shouldn’t let other people’s opinions of how smart or enthusiastic you are affect how much you contribute. | |

| IRMF3 | I’m really happy with myself. I take pride in my work. I’m not ashamed of doing well because of what people might think. Other people’s opinions wouldn’t stop me from doing well because there will always be people like me. |

Note: Participant ID is country code (IR=Ireland), age group (E = elementary, M = middle, H = high), sex (F = Female, M = Male), and subject reference number (1–3).

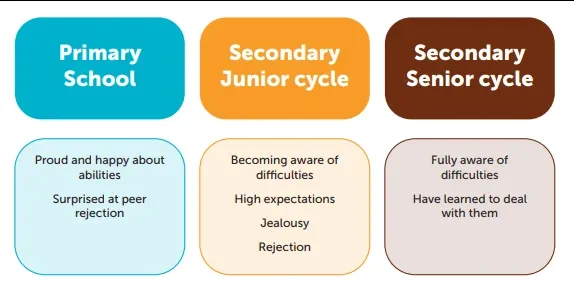

We did find an age-related pattern among the gifted students participating in the study (see Figure 3.4). Elementary-aged students were proud of the recognition their outstanding abilities received. They were happy when their parents or teachers were proud of their achievements. By middle school, students began to express an awareness of problems associated with their abilities. They were subjected to higher expectations than peers from parents, teachers, and even classmates. They experienced peers’ jealousy, rejection, and demands for help. By high-school age, these high-ability students had learned to accept these difficulties and developed coping strategies for dealing with them. Importantly, the high school students in the cross-cultural study were participating in gifted programs at the time of the research. It is likely that some students who learn in middle school about the challenges of higher expectations and peer rejection or demandingness will decide to leave such programs. Better understanding these difficulties and creating more positive environments will help more students achieve to their potential.

Figure 3.4 - Coping with the Social Experience of Giftedness Over Time

The information gathered in the cross-cultural study made it possible to create a questionnaire that explored social experiences in greater depth, with a larger number of students. In 2018, CTYI students completed the Social Experiences of Gifted Students Scale (SEGSS), which asked the frequency and emotional response to 53 experiences. From the 53 items of the SEGSS, 7 factors were identified;

-

Top of the Class: Things that happen when smart; I perform better and other students know it.

-

Helping Expectations: My abilities lead others to expect sharing/helping; associated with their hurt feelings/envy.

-

More Serious: I don’t get them because I’m more serious.

-

Pressure to Achieve: Pressure from others to always do well and be right.

-

Peer Rejection: I was rejected or made fun of.

-

Adult Expectations: Teachers and parents expect me to excel.

-

Hiding: Hiding behaviors so as not to be seen as different.

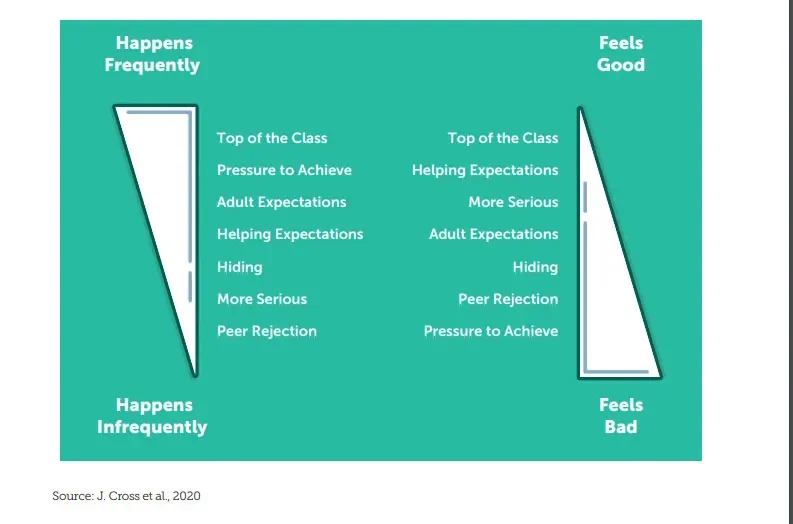

The most frequent experiences were related to being visible for their abilities, Top of the Class. These experiences were associated with the most positive feelings (Figure 3.10). CTYI students frequently experienced pressure from others to always do well and always be right (Pressure to Achieve) and this pressure was the experience that felt worst to the female CTYI students. Adult Expectations from parents and teachers to do well in school were frequent, but did not feel bad. Expectations that they would help peers occurred once in a while. For males, especially, this was associated with particularly good feelings. CTYI students had experienced the need to hide their abilities – less often for males than females and nonconforming students. It was not such a negative feeling for males. More Serious items were associated with confusion about other students’ behavior – it made no sense that others wanted to get out of schoolwork or copy theirs. This happened sometimes, but not often. It felt mostly good when it did occur. Fortunately, CTYI students reported that Peer Rejection occurred infrequently, but this was accompanied by bad feelings.

Figure 3.10 - Graphic Portrayal of Social Experiences Frequency and Feeling (2018 CTYI Students)

Students were asked to “Please share below any comments about the experiences listed above or any other social experiences related to your high academic abilities.” Through these comments (see Table 3.4), we see clear support for the experiences identified in the questionnaire. It is heartening that many students have positive social experiences in school (see the “All Good” section in Table 3.4), which can challenge the stereotype of the isolated, rejected “nerd”. We know that a majority of students at CTYI are not likely to be socially awkward, based on the analysis of personality and self-efficacy in Chapter 2, but the experiences and emotions of those who do not have a resilient personality or high self-efficacy are important to understand.

| Year in School | Sex | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Top of Class | ||

| 3 | Female | I stand out. People, particularly my peers, expect me to never be wrong. It is a lot of pressure and can make me stressed or depressed. |

| 3 | Male | In some groups it’s an annoyance to have to use simpler vocabulary and act |

| 2 | Female | I am often criticised for enjoying learning |

| 2 | Female | Everyone hated me in school because I read books |

| 5 | Male | I wouldn’t try answering a question I was not certain of the answer as if I’m wrong I often feel like the class gets excited at the act I was wrong. Makes me feel awkward embarrassed and that this is unfair. I should feel comfortable suggesting an answer I was unsure of. |

| 6 | Female | I don’t like feeling pressured or feeling like I’m under a microscope. Sometimes people do better in tests and they shove it in my face because I’m the smart kid. I can’t get 100% all the time despite what people may think. But I love helping people and I don’t like to share any results so no one feels bad. Sometimes I study for half an hour and I get a B and they study for days and get a B. It’s not what either of us are worth, it’s just a B |

| 5 | Female | There were no classes for more advanced students. I am always forced into a class with people who are at a slower pace than me |

| 2 | Female | I used to act like I didn’t study because people would laugh at me for it. |

| Pressure to Achieve | ||

| 1 | Female | When I get a lower result than what my friends expected me to get, I felt really disappointed. Sometimes my friends would playfully say that like “you’ll be fine you have probably been up late all night studying!” I know they are only playing but sometimes it’s just a little frustrating |

| 2 | Female | I do have quite a few friends but I do feel sometimes that people don’t like me and I often feel pressured to do well in school |

| 5 | Female | Felt pressure to constantly succeed or like there was an expectation to always be the best academically but never got much praise or encouragement |

| 3 | Male | People put too much pressure on me to get things right |

| 4 | Female | I feel under a lot of pressure about exams and tests and I sometimes think it makes me do worse |

| 3 | Female | My teachers push me a lot, resulting in me sometimes breaking down |

| 3 | Female | I stand out. People, particularly my peers, expect me to never be wrong. It is a lot of pressure and can make me stressed or depressed. |

| 1 | Male | Other students often expect that I get everything correct/ high school/grade. I enjoy CTYI because it allows me to meet a lot of great minds and intellectuals. |

| 2 | Female | Teachers & parents often put unnecessary pressure on us |

| 3 | Female | Everyone in school knows I’m smart but don’t really care other than always expecting me to get everything right. It’s annoying being in a school where everybody is fairly stupid. They don’t care about their education and get in the way of my learning new topics. |

| 5 | Male | It stresses me out that I care more about doing well on tests & studying than my friends do. It really stresses me out when I perform below the high expectations that I have of myself. |

| 5 | Female | People like me for me, mostly not my brain, though I felt great pressure to perform (esp. in JC) |

| 3 | Female | I don’t like girls in my school constantly needing to know my grades because I feel bad if they don’t do as well as me. Girls always expect me to get so high and roll their eyes at me if I meet their expectations. I’m scared people will think of me differently if I tell them my grades. |

| 4 | Female | I don’t have extremely high academic ability. I would not care about this so much, only everyone seems to overestimate my abilities. When my parents, teachers or peers mention how “smart” I am, I feel as though I’m letting them down. This has begun to bleed into other aspects of my life, and now I often find that I am critical of my abilities to do even the simplest of tasks. |

| 3 | I was better than the majority of my class but there were two better than me and I was quite worried that I would measure up. I was also under pressure from my family to socialise more. | |

| 3 | Female | Classmates expect a lot from me academically. |

| 3 | Female | People make fun of me for using big words. I hate it. People expect me to do amazingly but I can’t. People always ask to copy my work and I don’t know how to say no. |

| 1 | Female | I get annoyed when people expect me to be perfect at everything |

| 4 | Female | A lot of things only happened in primary school. But I think that is because my secondary school has an academic scholarship programme so people in my school don’t really care as much about if someone is gifted. They admire people’s talents rather than get jealous and be hurtful. In relation to other people’s academic talents I rarely measure others up to myself and how they do academically has no bearing on my feelings. I do however measure myself up to others and am often upset when I don’t do as well as I think I should |

| 4 | Female | I’m just a private and quiet person. I don’t talk much to my classmates unless they’re good friends (about my achievements). I don’t know if they’re jealous. My biggest issue is that they sometimes view my level as something good to pass or overtake, like if I don’t bother and I get a C, people are surprised and say, “Oh wow I did better.” |

| 2 | Female | My friends often expect/predict that I would get high scores on tests. |

| Adult Expectations | ||

| 2 | Female | When people (parents or teachers) expected me to do well it made me work harder and I felt happy that they had expectations of me |

| 5 | Male | I enjoy helping. I never really care what people think. People have high expectations that I fail to meet often. |

| 4 | Female | I go to a quite academic school, and while others are praised for doing well, for me it is expected. |

| 3 | Female | People just expect you to do well sometimes idk |

| Helping Expectations | ||

| 3 | Female | I like to feel challenged academically, I enjoy people having high standards of me and don’t mind showing my academic ability as it is something I am proud of and embrace. I am happy to help classmates who struggle and do not mind them putting high expectations on me as it is a challenge I strive to meet. I never try to hide or feel embarrassed of my academic ability |

| 2 | Female | People copy my work, but I know it’s because I will probably get the answers right. People assume that I will get high grades etc. and that makes me feel stressed. |

| 2 | Female | Some people in school hardly speak to me except to ask me for answers |

| 3 | Female | Sometimes I’d be saying something and my friends would stop me and go “Ok. I don’t understand.” or “English, please.” I feel like I am known for being smart. “Of course you didn’t find it hard”, “Let me look at your homework/ Can you help me do this?/ What do I do?”`` |

| 2 | Female | I suffer from Asperger’s so I’ve always found it hard to make friends and understand people’s feelings. I have regularly been asked to let someone copy my homework. I feel different from groups at school but in CTYI everyone is friendly and understandable |

| 1 | Female | I hate when people ask me what I get in tests, they look at me weirdly. I don’t tell them because I don’t want them to feel bad. I also hate when people ask to copy my homework. |

| 3 | Female | Many times people in my class have tried to copy my work. I never give them the answers. I try to help them through the work while allowing them to do it themselves. I then feel good because I have helped someone understand something |

| 4 | Female | I used to feel like the only reason people would come up and talk to me was because they wanted to copy my homework or ask me how to do something related to school work. I didn’t think that they really liked me, or wanted to talk to me. It’s alright now though. |

| Hiding | ||

| 3 | Female | Some people just won’t like you if you’re smart. It makes it easy to be self-deprecating to fit in. |

| 3 | Male | In some groups it’s an annoyance to have to use simpler vocabulary and act |

| 1 | Female | I changed my answers to the wrong ones in a Drumcondra test to fit in with my friends (a long time ago) |

| 2 | Female | I used to act like I didn’t study because people would laugh at me for it. |

| 2 | Female | I try not to do too well in school so I don’t offend/annoy people. I am not the only smart person in my class. |

| 3 | Female | I don’t like girls in my school constantly needing to know my grades because I feel bad if they don’t do as well as me. Girls always expect me to get so high and roll their eyes at me if I meet their expectations. I’m scared people will think of me differently if I tell them my grades |

| 2 | Female | I tried to hide my academic abilities so others would not treat me differently. I moved schools in 4th class but before I moved the teacher and students always expected me to study all the time and love homework so I always got extra homework. When I moved school I tried hiding my abilities so I could be like everyone else |

| 3 | Male | Often I don’t want to brag if I get good grades because I’m afraid the friends I do have will get annoyed so I often keep quiet. I feel like I’m holding myself back and I hate being isolated when I didn’t want to be. That’s why I love CTYI because there are so many likeminded people. I can openly be myself and have good conversations with everyone. I don’t usually feel pressure from my parents or teachers but I often feel because I usually get good grades that my standards have raised so much I feel I’m disappointing people if I don’t do well. People could often say I thought you were smart and it hurts my feelings. |

| 2 | Female | I tend to avoid competition so as to not being comparing myself to others. As well as this, I simultaneously try to hide myself and show myself off (in school, academically) so as to receive more challenge, but privately, with us ~competition~ from others (e.g., spelling bee) is not a “fun” challenge. |

| 2 | Female | I feel like a ‘misfit’ at school and I have a few friends, and when I talk to them, I have to ‘dumb down.’ Whenever I get good scores I try to hide them, but the other students find out anyway. I am envied for this but I feel horrible as I am treated very differently, like an outsider |

| 3 | Female | I basically suppressed my abilities from 3rd class until 2nd year |

| More Serious | ||

| 3 | Female | I feel like my experiences were very different to a good few of the questions as my grades aren’t the best, I’m just mature and a lot of the time I get annoyed at all the stupid drama school friends were creating but that’s the extent of it. |

| 4 | Male | I have never cared about anyone’s feelings or opinions of me regarding my ability academically or physically because those people lack any trait I value and are essentially useless |

| 1 | Male | Being so smart leads to power, and with power comes greed. Many of my classmates were jealous of my academic abilities and used to bully me quite a bit. Eventually they were used to it and didn’t mind it. |

| 3 | Female | Everyone in school knows I’m smart but don’t really care other than always expecting me to get everything right. It’s annoying being in a school where everybody is fairly stupid. They don’t care about their education and get in the way of my learning new topics. |

| 4 | Male | I’ve never been good at socializing but I’m getting better. I generally don’t care what others think about me, they all have relationships and go to discos, but I don’t do that stuff. |

| 5 | Female | Although I have had experiences with jealous students since primary school, as a whole, I have had good experiences with the vast majority of students. I have struggled with jealous students all my life. I’d be much harder on myself and my grades than any of my teachers or my parents |

| 2 | Female | People copy homework A LOT. And they (immediately after we get tests results back) ask me what I got, and assume that I spend my life studying, when really I just retain information rather easily, and actually enjoy school/homework/learning. If I get an A, they judge. If I get a B, they also judge. It’s like they can’t handle me doing good nor bad. School is sometimes annoying because we have to go at a slow pace sometimes, and it gets boring having to repeat simple concepts. That’s why CTYI is so good - learning is intense and work is challenging (a dream come true compared to real school! :)) |

| Peer Rejection | ||

| 2 | Female | I don’t really like sharing my scores because I don’t think it adds or subtracts from anything, from who I am, and I know others do care and I don’t want to make them feel bad |

| 6 | Male | Lack of interests in common leads to social isolation |

| 2 | Female | Some people in school hardly speak to me except to ask me for answers |

| 3 | Female | Sometimes people treat me differently because I’m intelligent. They don’t accept me in their circle. |

| 5 | Male | Certain other students become enraged at me, become aggressive over envy of my academic ability |

| 1 | Female | I changed my answers to the wrong ones in a Drumcondra test to fit in with my friends (a long time ago) |

| 3 | Male | Being sporty I was able to be more socially in tune than others of my academic ability |

| 3 | Male | Other people treat you like you are different and make fun of you. |

| 2 | Female | I do have quite a few friends but I do feel sometimes that people don’t like me and I often feel pressured to do well in school |

| 2 | Male | Yes; outcast in school, focuses energy on dreams and wishes, most friends are close, few acquaints |

| 2 | Female | I won a maths competition and everyone was talking about me badly and being jealous, until they heard the prize was only a maths book. |

| 2 | Female | I used to act like I didn’t study because people would laugh at me for it |

| 3 | Male | I went to a very small primary school where I was bullied a lot and had no friends but my social skills have been getting better |

| 6 | Male | School is depressing and lonely. 5th year was a totally exhausting experience. |

| 2 | Female | I am often criticised for enjoying learning |

| 3 | Female | Some people just won’t like you if you’re smart. It makes it easy to be self-deprecating to fit in. |

| 3 | Male | The Centre for Talented Youth, Ireland has relieved a lot of the worries pertaining to the social aspects. It allowed me to connect with other intellectuals of the same age. Ergo, I have a lot more likeminded individuals in my proverbial phonebook. |

| 2 | Female | I feel like a ‘misfit’ at school and I have a few friends, and when I talk to them, I have to ‘dumb down.’ Whenever I get good scores I try to hide them, but the other students find out anyway. I am envied for this but I feel horrible as I am treated very differently, like an outsider. |

| 2 | Male | It socially isolates you to be better at something no one cares about |

| 5 | Male | if you want to fit in you have to be not too smart or too stupid - not in ctyi |

| All Good | ||